I. A Brief History of ICE’s Creation and Mandate

The United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was born in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks. In November 2002, Congress passed the Homeland Security Act, leading to the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and a massive reorganization of federal agencies. When DHS officially opened in March 2003, it absorbed the enforcement functions of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (formerly under the Justice Department) and the investigative arm of the U.S. Customs Service (from the Treasury Department). These were merged into a new entity called the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement – soon renamed ICE. Lawmakers sought to give ICE a “unique combination of civil and criminal authorities” to protect national security and public safety. In effect, ICE became “the largest investigative arm” of DHS, empowered to enforce immigration laws in the U.S. interior while also tackling customs violations and transnational crime.

ICE’s stated mission is “to protect the United States from transnational crime and illegal immigration that threaten national security and public safety.” In practice, ICE is a broad law enforcement agency with two primary divisions. Its Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) branch focuses on finding, detaining, and deporting undocumented immigrants. The other branch, Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), pursues a wide range of criminal offenses – from human smuggling and drug trafficking to cybercrime and child exploitation. This dual role means ICE agents might in one case be raiding a location to arrest immigration violators, and in another case dismantling a money-laundering network or busting a child pornography ring. Over 400 federal statutes fall under ICE’s jurisdiction, reflecting its expansive mandate.

From its inception, ICE evolved rapidly. In its first year (2003), the new agency set up fugitive operations teams to track down noncitizens with outstanding removal orders, launched “Operation Predator” to combat child sex crimes, and began forging its identity as a post-9/11 enforcement arm. The early years saw a focus on national security threats, such as investigating potential terrorists and enhancing visa security, alongside traditional immigration enforcement. By the mid-2000s, ICE was conducting high-profile worksite raids to arrest undocumented workers and their employers. For example, large-scale immigration raids at meatpacking plants and factories made headlines in the Bush administration, underscoring ICE’s interior enforcement mission.

Policy priorities shifted with each administration. Under President George W. Bush, ICE was aggressive in enforcement but also introduced programs like “Alternatives to Detention” using electronic monitoring for some immigrants. The Obama administration, by contrast, recalibrated ICE’s approach: resources were directed to focus on those with serious criminal records, and programs like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in 2012 signaled a more lenient approach for certain populations. Large workplace raids were scaled back; instead, ICE increased audits of employer I-9 forms and launched the Priority Enforcement Program to target felons over non-criminals. Nevertheless, ICE still deported hundreds of thousands annually during the early 2010s, earning President Obama the moniker “Deporter-in-Chief” from some advocacy groups. The agency’s mandate did not shrink, but its tactical emphasis shifted to align with policy guidance that prioritized public safety threats over non-violent immigration violators.

A major transformation came with the Trump administration’s first term (2017–2021). President Donald Trump removed the prior prioritization guidelines and essentially made all undocumented immigrants fair game for arrest. ICE arrests surged in 2017, including “collateral” arrests (detaining undocumented people encountered even if they were not the original target). This era brought ICE into the political spotlight like never before. The agency’s aggressive tactics – such as arresting parents outside schools and courthouses – sparked public outcry, especially in “sanctuary” jurisdictions. An “Abolish ICE” movement even emerged on the left, reflecting a view that ICE’s post-9/11 incarnation had overstepped humane bounds. By 2018, ICE’s image had become “one of the most public and contentious functions” of DHS. Still, supporters argued ICE was simply enforcing laws that Congress enacted, and pointed to its role in arresting gang members and serious criminals.

The pendulum swung again under President Joe Biden (2021–2024). Biden’s DHS leadership imposed strict priorities for ICE, instructing officers to focus on recent border-crossers and those posing national security or serious criminal threats. They also issued a “protected areas” policy (October 2021) forbidding enforcement actions at sensitive locations like schools, hospitals, places of worship, and courts absent special circumstances. By 2022, ICE arrests and deportations had dropped significantly compared to the Trump years, and the administration sought to rebuild community trust. However, Biden’s approach faced legal challenges from some Republican-led states and internal pushback. Notably, in mid-2022 a federal court blocked Biden’s enforcement guidelines, yet ICE still exercised more discretion than before. The cumulative effect was that by late 2024, ICE’s enforcement tempo and public profile had been comparatively lower, even as border crossings remained a contentious political issue.

Heading into 2025, ICE was at a crossroads. It had been two decades since its creation, and the agency’s identity was pulled in opposite directions by changing political winds. One side saw ICE as vital to upholding the rule of law and ensuring immigration system integrity; the other saw it as an agency in need of reform – or even abolition – due to perceived abuses. This tension set the stage for what would follow in early 2025, when a new administration dramatically changed ICE’s marching orders yet again.

II. The 2025 Shift: A New Era of Aggressive Enforcement

In January 2025, President Donald Trump returned to office, bringing with him a hardline immigration agenda even more uncompromising than in his first term. Within days, ICE’s posture shifted from the quieter approach of the late Biden years to an unabashed crackdown. Official directives rescinded the prior administration’s policies and expanded ICE’s operational latitude:

- Protected Areas Policy Rescinded: On January 20, 2025 – literally within hours of inauguration – DHS issued a directive cancelling the Biden-era rules that had barred ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) from making arrests in “protected areas” like schools, hospitals, courthouses, and churches. Henceforth, officers were simply advised to use “discretion” and “common sense” regarding enforcement in sensitive locations, rather than being constrained by any blanket prohibition. ICE followed up with its own interim guidance allowing civil immigration arrests at courthouses when agents have credible information a target will be present – provided they coordinate with legal counsel and, if possible, conduct the action discreetly in non-public areas. By month’s end, ICE leadership essentially told field officers that decisions on where and when to make arrests (even in former off-limit zones) would be left to their case-by-case judgment. The immediate practical effect was to green-light ICE operations in places that had been mostly off-limits for the previous three years. (Notably, one federal court did step in by March 2025 to partially enjoin this policy as it applied to places of worship, ordering ICE to abide by the old rules at listed churches and temples unless armed with a warrant. But apart from this injunction covering religious sites, the expansive new approach to enforcement locations went forward.)

- Arrest Quotas and Expanded Dragnet: The new administration also set numerical expectations reflecting its drive for mass deportation. Internal communications in late January indicated ICE was directed to meet daily arrest quotas of 1,200 to 1,500 individuals. By late May, this target grew even more ambitious: DHS Secretary Kristi Noem and White House advisor Stephen Miller reportedly berated ICE leadership and demanded at least 3,000 arrests per day, or roughly one million per year. Field office managers were instructed to “turn the creative knob up to 11” to find and arrest as many deportable immigrants as possible. This included arresting “collaterals,” meaning people encountered incidentally during operations who weren’t original targets. Under prior practice, ICE would often bypass such individuals unless they posed a threat, focusing instead on specific fugitives or criminal aliens. Now, agents were explicitly told to maximize arrests – even of those with no criminal record – to boost the numbers. As one research professor observed, “The data reflects … ICE is in the community, arresting an awful lot of people who don’t have criminal histories. It doesn’t reflect what the agency claimed they’re doing, which is going after the hardened criminals first.” Indeed, by June 2025, analysis showed an 807% increase in arrests of immigrants with no criminal record compared to the start of the year. This sharply contradicted President Trump’s public insistence that ICE was targeting “criminals” for deportation. In reality, being undocumented (a civil violation) was enough to land someone in ICE custody, even if they had lived peacefully in the U.S. for years.

- More Boots on the Ground: To achieve these goals, the administration surged resources into interior enforcement. ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations got a boost in staffing, and significantly, other federal agencies’ agents were deputized to augment ICE. Special agents from the FBI, DEA, ATF, and even HSI (which normally focuses on crimes, not civil immigration violations) were directed to assist in immigration enforcement sweeps. At the same time, DHS dramatically expanded partnerships with local and state law enforcement. The number of jurisdictions participating in the 287(g) program – which empowers local police to act as immigration agents – reportedly tripled in the first half of 2025. Florida’s governor noted his state “leads the nation with 287(g) partnerships” and framed local involvement as a “force-multiplying” of ICE’s efforts. This outsourcing of immigration duties to other agencies raised some transparency concerns, since arrests were sometimes carried out by agents in other uniforms (or in plainclothes), blurring lines of authority. But it undeniably extended ICE’s reach. By June 1, 2025, ICE’s detained population exceeded 51,000 – the highest number in U.S. immigration jails since 2019.

- Legal Maneuvers and Emergency Powers: The administration also pushed the envelope in using extraordinary legal authorities to speed up removals. In March 2025, President Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 (AEA) – a rarely used wartime statute – as a tool to deport certain groups of noncitizens without the usual due process. Specifically, Trump issued a proclamation designating the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua as a “foreign terrorist organization” and deeming its suspected members as alien enemies subject to immediate removal. Under this invocation, ICE began fast-tracking deportations of hundreds of Venezuelan men alleged (often on shaky evidence) to belong to the gang. Many were whisked onto planes and sent not to Venezuela (which has no diplomatic relations with the U.S.), but to a mega-prison in El Salvador under a deal where the U.S. pays El Salvador to hold them. Civil liberties groups were alarmed. The ACLU argued it was “unlawful and unprecedented” to use a 18th-century wartime law to bypass immigration courts. Lawsuits flew in multiple jurisdictions. While several federal judges (in New York, Colorado, and Texas) ruled against Trump’s use of the AEA, one judge in Pennsylvania upheld it with conditions. That judge acknowledged the President’s authority to invoke the act but ordered the government to provide at least 21 days’ notice and an opportunity to challenge for those targeted – to avoid “errantly” deporting people who were not actually gang members. She also criticized reports of people being deported “within a matter of hours,” urging more process. Despite judicial objections, the administration signaled intent to continue using every available power. Human Rights Watch warned that the 1798 law is a “dangerous instrument” prone to abuse and urged Congress to repeal it. By mid-2025, the AEA issue remained tied up in courts and political debate, emblematic of how far the government was willing to go to accelerate deportations.

All these measures combined to create an atmosphere in 2025 of unprecedented immigration enforcement intensity in the U.S. interior. ICE was making more arrests in city streets, homes, and even courthouses than at any time in recent memory. And the push was coming straight from the top: President Trump openly promised “mass deportations” and castigated any local or state officials who stood in the way. The stage was set for a series of confrontations and controversies that would test the balance between enforcing immigration laws and upholding the rule of law itself.

III. Major Operations and Flashpoints (Jan–June 2025)

The first half of 2025 saw a flurry of ICE operations – some planned enforcement surges, others unfolding chaotically amid public backlash. Below is a timeline of key incidents and shifts in ICE strategy during this period:

| Date | Incident or Change | Description & Significance |

| Jan 20, 2025 | “Protected Areas” Policy Rescinded | DHS rescinds the 2021 policy that limited ICE/CBP actions at sensitive locations (schools, hospitals, churches, etc.), urging agents to use discretion instead. This effectively removes prior sanctuary zones, allowing ICE courthouse and neighborhood arrests that were previously off-limits. |

| Jan 31, 2025 | Arrest Quotas Introduced | The Trump administration directs ICE to meet daily arrest quotas of 1,200–1,500 people. By late May, officials demand 3,000 arrests per day, leading to widespread “collateral” arrests of immigrants with no criminal history (807% increase). |

| Mar 15, 2025 | Alien Enemies Act Invoked | President Trump invokes the 1798 Alien Enemies Act to fast-track deportations of alleged members of Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua gang. Detainees are deported to an El Salvador prison via a U.S.-funded arrangement. Courts and advocates challenge this peacetime use of a wartime law. |

| Apr 21–26, 2025 | “Operation Tidal Wave” in Florida | ICE and Florida state authorities conduct the largest joint immigration sweep in Florida’s history, arresting 1,120 people in one week. About 63% had criminal records; others were picked up for civil immigration violations. Gov. Ron DeSantis hails the operation as “delivering on the 2024 mandate” to secure borders. |

| May 9, 2025 | Newark Mayor Arrested | Newark, NJ Mayor Ras Baraka is arrested and charged with trespassing while visiting a privately run immigration detention center to protest or observe conditions. Though charges against the mayor are later dropped, a local Congresswoman who intervened (Rep. LaMonica McIver) is charged with assaulting officers. The incident highlights tensions between ICE/detention contractors and local elected officials. |

| June 5–7, 2025 | Los Angeles Raids and Protests | ICE conducts large-scale enforcement raids around Los Angeles (targeting day labor sites, a garment factory, etc.), arresting at least 44 people in one day. Protests erupt in the city; some turn heated with overturned carts and tear gas on the streets. The White House deploys 2,000 National Guard troops without the Governor’s consent, sparking legal and political battles over federal overreach. |

| June 12, 2025 | Senator Padilla Detained in LA | During a DHS press conference in Los Angeles about the raids, U.S. Senator Alex Padilla (D-CA) attempts to ask Secretary Noem a question. Security agents shove Padilla to the ground and handcuff him, mistaking him (they claim) for a threat. He is released within minutes. The shocking treatment of a sitting Senator fuels accusations of “totalitarian” behavior by the administration. |

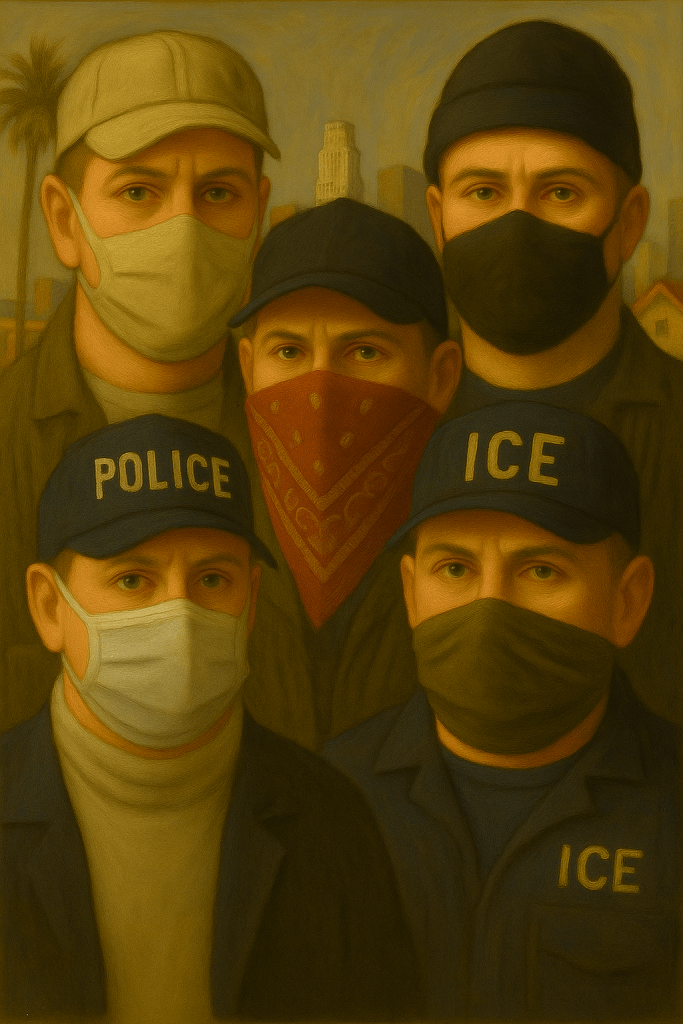

| June 17, 2025 | NYC Mayoral Candidate Arrested | New York City Comptroller Brad Lander, a Democratic mayoral candidate, is handcuffed and detained by ICE agents at a Manhattan immigration court. Lander was accompanying an immigrant to a hearing when agents in plainclothes and surgical masks grabbed him. DHS accuses Lander of “assaulting” an officer, a charge he vehemently denies. He is released hours later after New York’s governor intervenes, and the incident ignites debate about ICE’s presence in courthouses and potential political intimidation. |

These incidents illustrate the unfolding narrative of 2025: an ICE emboldened to carry out sweeping enforcement, and a growing backlash from politicians, activists, and community members who view some of these actions as abuses of power. In examining them more closely, several themes and patterns emerge.

Clashes with Local Authorities and Politicians

Perhaps the most dramatic new pattern in 2025 has been the direct confrontations between ICE (or allied federal agents) and elected officials who oppose aspects of the crackdown. The federal government under Trump signaled zero tolerance not only for undocumented immigrants, but also for public servants deemed to be “getting in the way” of enforcement. In fact, in Trump’s first week back, his administration ominously warned it would “investigate officials” who resist his immigration agenda. By spring, that threat was being acted upon:

- In Newark, Mayor Ras Baraka’s arrest while visiting a detention center demonstrated an aggressive posture toward local leaders. Baraka has been an outspoken critic of ICE’s contract detention facility in his area. His being led away in handcuffs was widely seen as a message that even mayors could face consequences for challenging immigration authorities. (Although charges were dropped, the episode had a chilling effect.) The fact that a U.S. Representative, LaMonica McIver, was charged with crimes for allegedly trying to stop Baraka’s arrest only amplified the sense of escalation. Both Baraka and McIver maintain they did nothing wrong, and their allies contend the charges were trumped-up. “This is a sad and frightening state of affairs,” Rep. McIver said, accusing the administration of trying to “keep elected officials from doing our jobs…They don’t want oversight, they want total control.”

- In Los Angeles, Senator Alex Padilla’s ordeal on June 12 became a national flashpoint. Padilla (formerly California’s Secretary of State, now a U.S. Senator) showed up at Secretary Noem’s press event to demand answers about ICE tactics in his state. Video he released shows him calmly stating, “I have questions for the Secretary,” before being forcefully grabbed. Three agents slammed the Senator – a 52-year-old man – onto the floor and cuffed him. DHS later tried to justify the incident by labeling Padilla’s act “disrespectful political theater,” claiming agents thought he was an “attacker” and acted for Noem’s security. The FBI’s Deputy Director (and prominent Trump ally) Dan Bongino also chimed in that Padilla wasn’t wearing the special lapel pin that identifies members of Congress, implying agents didn’t know who he was. Padilla, once released, was furious. “If this is how DHS responds to a Senator with a question,” he said, “imagine what they’re doing to farmers, to cooks, to day-laborers…throughout the country.” His point was clear: if federal agents could rough up an elected lawmaker in public, it suggested a broader climate of heavy-handedness. On Capitol Hill, outrage ensued. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said the footage “reeks of totalitarianism.” Senator Cory Booker noted this was “not an isolated incident” but part of a pattern (citing what happened in Newark). Even a Republican, Senator Lisa Murkowski, broke ranks to criticize Padilla’s treatment as “wrong and sick”, remarking on how disturbing it was to watch a big man like Padilla manhandled in that way. The White House, however, doubled down—far from apologizing, President Trump said days later he’d “support the arrest” of California’s Governor Gavin Newsom as well, after Newsom condemned the deployment of troops to LA as unlawful. Such rhetoric was virtually unprecedented in modern U.S. politics: a President musing about having a sitting governor arrested.

- In New York City, the arrest of Comptroller Brad Lander on June 17 added another example of ICE’s confrontations with politicians. Lander, akin to a city’s chief financial officer, is an elected official and at the time a candidate for mayor. He had made a point of escorting immigrants to their court dates as an act of solidarity and oversight. On that day, as Lander accompanied a client at a federal immigration court in Manhattan, plainclothes ICE agents took him into custody in a hallway. Witness video (which Lander himself posted) showed agents in baseball caps and surgical masks twisting Lander’s arms behind his back and leading him away, as he yelled “I’m a city official!”. One of the men wore a vest reading “Police Federal Agent,” but the overall scene was chaotic and secretive – agents did not clearly identify themselves or their agency at first, and their use of Covid-style masks obscured their faces. DHS later alleged that Lander “assaulted” law enforcement and “impeded” an officer. In the heat of the moment, they accused him of literally laying hands on an agent, hence justifying the arrest. Lander absolutely denied this: “I certainly did not assault an officer,” he told reporters. Notably, New York Governor Kathy Hochul rushed to the courthouse upon hearing of the incident and personally intervened to get Lander released without charges. An infuriated Hochul called the arrest “bullshit” as she escorted Lander out. She demanded to know “How dare they?” arrest an elected official performing his duties, suggesting ICE had crossed a line. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Manhattan said it would be reviewing Lander’s actions, though many observers suspected the bigger issue was ICE’s actions. This episode raised serious questions: Was ICE using legitimate obstruction charges, or was this a form of political retribution against a vocal critic of the administration’s tactics?

In all these cases, ICE and DHS defended their agents’ conduct as lawful enforcement. They maintain that no one is above the law – not mayors, not senators – if they interfere or break rules. “No one is above the law, and if you lay a hand on a law enforcement officer, you will face consequences,” declared DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin in response to Lander’s case. Similarly, DHS implied Padilla’s removal was standard procedure for an “unruly” person breaching security protocol. However, critics see a pattern of overreach: federal agents seemingly quick to use force and legal threats against democratic officials from the opposition party. It’s an extraordinarily fraught development in American governance when the enforcers and the elected start physically tussling. Many are asking: Are these legitimate law enforcement actions, or are they edging into authoritarian territory by targeting political dissent?

ICE on the Streets: Aggressive Tactics and Public Safety Concerns

While political dramas played out, ICE was also making its presence felt in communities through large-scale operations. The return to high-profile raids and heavy force marked another contrast with the recent past. Under Biden, workplace raids had been largely halted; under Trump in 2025, worksite and neighborhood raids came roaring back, sometimes with hundreds of agents involved.

One prominent example was Operation Tidal Wave in Florida (April 21–26, 2025). Billed as a “whole-of-government” sweep, this joint ICE-state effort led to 1,120 arrests statewide in just one week. DHS touted it as the largest such operation in ICE’s history for a single state. It targeted people with outstanding deportation orders, as well as those with criminal backgrounds. According to ICE, 63% of those arrested had prior criminal arrests or convictions – meaning, conversely, roughly 37% had no criminal record beyond civil immigration violations. Those included individuals whose only “crime” was re-entering the U.S. after a deportation (a felony under immigration law) or simply overstaying a visa (a civil offense). The operation netted a wide array of people: “violent offenders, gang members, sex offenders… and those who pose significant public safety threats,” as well as fugitives with final deportation orders. ICE highlighted the arrest of alleged members of MS-13 and other gangs to underscore the public safety angle. Governor DeSantis cheered the results, framing Florida as “the tip of the spear” in supporting federal immigration enforcement. He thanked ICE and even Florida’s Fish and Wildlife officers and National Guard for their contributions – indicating just how many arms of law enforcement were mobilized. For supporters, this operation was ICE at its best: coordinating seamlessly with local authorities to “restore integrity” to the system and remove dangerous criminals. For critics, it exemplified the broad net being cast: hundreds of people swept up, families separated, and nearly half of those arrested not obviously “dangerous” at all (the 37% with no known criminal history). The heavy involvement of state resources also raised eyebrows; it blurred the line between federal and local policing and made the state of Florida an active enforcer of federal immigration law, a role some states refuse to take.

An even more kinetic operation unfolded in early June outside Charleston, South Carolina, with a dramatic raid on an alleged cartel-run nightclub. Acting on a tip about a clandestine club known as “The Alamo,” ICE’s HSI agents obtained a federal search warrant and, with ATF and local police backup, stormed the establishment during a weekend operation. They anticipated finding weapons, narcotics, and evidence of human trafficking – and indeed seized illegal guns, drugs, and cash on the scene. In the process, they arrested 72 individuals present, including patrons and staff. Among them was a high-profile catch: a Honduran national wanted for homicide on an Interpol Red Notice. They also rescued six underage trafficking victims and turned them over to social services. DHS leadership hailed this raid as a prime example of why robust immigration enforcement matters. The club operator was allegedly linked to the Los Zetas cartel (rebranded as Cartel Del Noreste), which the administration had designated as a terrorist organization just months prior. “Under President Trump and Secretary Noem, fugitives and lawbreakers are on notice: Leave now or ICE will find you and deport you,” declared Assistant Secretary McLaughlin after the raid. This operation had all the elements of a lawful, well-coordinated strike: judicially approved warrant, clear criminal targets, multi-agency cooperation, and tangible community protection outcomes (removing violent offenders and protecting victims). Even some immigration skeptics acknowledged this is the sort of work ICE is unequivocally expected to do – arresting “an international murder suspect” and busting a criminal ring. By highlighting such successes, ICE seeks to justify the broader crackdown. However, it’s worth noting that out of the 72 arrested at the club, not all were hardened criminals; some were likely simple undocumented attendees caught in the dragnet. Still, in cases like this Charleston raid, the benefit to public safety is evident and largely uncontested.

ICE’s ramped-up activity also extended to less dramatic but symbolically significant actions, like workplace inspections and small-scale roundups. For instance, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, ICE and labor investigators conducted a surprise audit at a factory in mid-June, resulting in 17 workers being detained for immigration violations (a throwback to the “silent raids” of paperwork audits favored in the late 2000s). In New York’s Hudson Valley, ICE arrested a noncitizen with prior DUI convictions, highlighting that under new priorities even past misdemeanors made someone a target for deportation. And in Nebraska, ICE used video evidence to identify and arrest several protesters who had vandalized property and allegedly threatened officers after an immigration raid – then blasted out a press release with “caught on camera” footage to deter others. In that Nebraska case, ICE emphasized that while it respects peaceful protest, it “will not tolerate… abuse, intimidation, and lawlessness” against its officers. Those arrestees now face felony charges for assaulting federal officers and damaging property.

Taken together, these operations send a clear message: ICE in 2025 is everywhere. From rural nightclubs to urban courthouses, from factories to freeway checkpoints (which popped up more frequently near cities like Atlanta and Denver, per anecdotal reports), the agency has been executing a strategy of maximum pressure. To supporters of stricter immigration control, this has been a long-awaited return to enforcing the law without apology. They argue that for years, too many people evaded deportation due to political restraints; now, at last, ICE is empowered to do its job fully. They point to the surge in arrests of criminals, the seizure of drugs and guns, and the deterrent effect of visible enforcement. Indeed, by June, there were reports of undocumented families in some areas fleeing the state or hiding indoors, recalling the climate of fear during major 2017 ICE operations.

To critics, however, the human toll and potential overreach of this campaign are immense. They highlight cases like a U.S. citizen child in Los Angeles coming home from school to find her undocumented parents gone (detained by ICE that morning), or long-time residents with clean records suddenly being arrested during routine check-ins. Legal aid organizations say their caseloads have exploded, and due process is straining: with so many more detained, getting attorneys for each person or even basic legal screenings is difficult. Experts have warned that quotas and rushed proceedings could result in wrongful deportations – including of people with valid asylum claims or even, in rare but documented instances, U.S. citizens mistakenly caught up. The pace of enforcement has outmatched oversight mechanisms, raising the risk of abuses. An example is the transfer of detainees like A.S.R. (the Venezuelan man in Pennsylvania) out of jurisdictions despite court orders – a judge noted ICE moved him to Texas the same day a court barred his removal from that district. Such maneuvers give the impression of an agency sometimes operating first and answering questions later.

IV. Law vs. Ethics: Legal Authority and Public Backlash

A central tension in evaluating ICE’s 2025 activities is distinguishing what is formally legal from what many consider ethically or democratically troubling. The administration often defends its actions by pointing out they are authorized by law: immigration violations are indeed offenses that ICE is empowered to address; the President does have broad statutory authority over immigration enforcement; even calling in the National Guard to quell unrest, while extreme, can be framed in law-and-order terms. But critics argue that legality alone does not confer legitimacy when actions undermine fundamental norms or appear disproportionate.

For instance, are masked, plainclothes ICE agents grabbing a political figure in a courthouse legally permissible? Technically, yes – especially after Jan. 20, 2025, when courthouses ceased being off-limits. Federal officers can arrest someone if they have probable cause of a violation (here, they claim Lander interfered with an arrest). But the manner of Lander’s arrest – agents not readily identifiable as ICE, wearing surgical masks without a clear health need – led to accusations of lack of transparency and even comparisons to “secret police.” ICE officials counter that plainclothes operations are standard for certain units and that masks can be used for anonymity or health (some agents noted COVID-19 policies still allowed mask-wearing). Nevertheless, to the public, images matter. The video of Lander’s arrest looked more like a kidnapping than an official act, a perception ICE later tried to dispel by noting one agent’s vest said “Federal Agent”. The broader worry is that such tactics erode trust: if people cannot clearly recognize who is arresting whom and on what authority, it undermines the accountability that law enforcement in a democracy requires.

Another question: Is deploying military forces in Los Angeles to assist with civilian immigration enforcement legal? By the letter of federal law, the President can deploy the National Guard under Title 10 of U.S. Code or invoke the Insurrection Act to use active-duty troops for domestic law enforcement in certain conditions. In the LA case, Trump did not formally invoke the Insurrection Act, according to officials, but he did federalize National Guard units without the Governor’s consent. California’s state government filed suit, arguing this move violated state sovereignty and the Posse Comitatus Act (which bars using the Army/Air Force for law enforcement without explicit statutory authorization). The legal outcome is pending, but historical precedent is thin – the last time active-duty troops were used in LA was in 1992, and that was at the governor’s request during extreme riots. This time, the federal government acted over the state’s objections, in what Governor Newsom called “deranged behavior” and a political stunt. Ethically, even if some legal argument allows it, sending Marines in alongside ICE against what were mostly peaceful protestors crosses a normative line in many eyes. (As of mid-June, around 2,700 troops – Guard and some Marines – were in LA helping guard federal buildings, a scene Americans are not used to witnessing in their cities.)

The administration insists such measures are needed because, in its narrative, Los Angeles was in a state of insurrection. Trump and his allies described the protesters as “insurrectionists carrying foreign flags” (a reference to Mexican flags seen at rallies). Right-wing commentators even floated conspiracy theories that the unrest was fueled by outside agitators or foreign governments – a claim for which no evidence has emerged, but which circulated widely on social media. This highlights how misinformation has clouded the factual picture. The reality, as verified by local reporters and organizations like Newsguard, is that while there were some violent incidents (cars set on fire downtown, clashes in one neighborhood), most of LA was not a war zone. The confrontations were real but localized. Many posts online, however, painted the entire city as aflame, and even the White House amplified that view as justification for harsh measures. One viral tweet falsely claimed that pallets of bricks were dropped for protesters by “Soros-funded” groups – a recycled hoax from 2020 protests. Such distortions were “catnip for rightwing agitators,” as one Guardian piece put it, feeding into the administration’s law-and-order narrative. The danger is that speculation and spin can drive policy: if officials truly believe (or want the public to believe) they’re facing an “urban insurrection” rather than community protests, they will resort to extraordinary crackdowns. Impartial observers note that describing mostly unarmed protesters as an “insurrection” (a term traditionally reserved for attempts to overthrow the government) is a gross exaggeration. But it served the political purpose of framing any dissent against ICE raids as beyond the pale – even traitorous.

Legally, ICE’s core operations remain squarely rooted in the powers Congress has given it: to detain and deport those without legal status. Ethically, however, a host of questions arise from how those operations are conducted. Is it right to arrest people at courthouses – places that should be safe for people to access justice? ICE’s new courthouse policy says agents “should generally avoid” non-criminal court areas and be discreet, but Lander’s arrest occurred at an immigration court (where non-criminal civil proceedings happen), precisely the sort of place previously off-limits. Immigrant advocates argue that courthouse arrests have a chilling effect: immigrants might skip court dates (even for unrelated issues where they are victims or witnesses) out of fear of ICE, undermining the justice system. The counterargument is that some immigrants exploit courthouses to hide (knowing ICE was hands-off there under prior policy), and that coordinating with court security as ICE now pledges to do mitigates risk. Still, the optics of grabbing people at courthouses or outside hospitals remain unsettling to many Americans who, regardless of stance on illegal immigration, feel certain civic spaces should be sacrosanct.

Another legally grey area is cooperation with private detention centers and contractors. The Newark incident occurred at a privately-run ICE detention facility. These facilities often have their own security and rules (Baraka was technically trespassing if he entered a secure area without permission). But when an elected official is arrested for simply trying to inspect conditions or speak to detainees, it raises the issue of transparency in a system largely run by for-profit prison companies. ICE has faced lawsuits about abuses and negligent deaths in detention; oversight is crucial. Cutting off oversight by threatening local officials with arrest sends a troubling signal. Legally, the private security had the right to involve ICE or federal protective services if someone refused to leave their property. Yet ethically, one might ask: what were they trying to prevent the mayor from seeing or doing? This kind of clash fuels public distrust and the sense that ICE’s mandate (to detain immigrants) is being zealously enforced at the expense of accountability.

V. Balancing Security and Democratic Values

Through the turbulence of 2025, a throughline question persists: How do we balance the imperative of immigration control with the imperatives of American democratic values and the rule of law? As someone observing from beyond the U.S. border but deeply committed to the ideals at stake, I approach that question with both clarity and concern. Every sovereign nation, the United States included, has not only a right but a duty to control its borders and enforce its laws. Efficient, lawful enforcement of immigration rules is essential – it maintains order, prevents exploitation, and upholds the integrity of legal immigration pathways. In this sense, ICE’s mission is entirely legitimate. Many ICE officers and agents carry out difficult work – catching human traffickers, busting drug smuggling rings, removing truly dangerous felons – work that rarely makes the headlines but undeniably makes communities safer.

However, means matter just as much as ends in a democracy. Enforcement must be done lawfully, ethically, and transparently. What we have witnessed in the first half of 2025 is a series of actions that, while often grounded in some legal authority, appear to stretch the spirit of the law and flout the norms of accountable policing. When ICE agents wear masks and shove an elected representative to the ground, it is technically “law enforcement,” but it doesn’t look like the United States of America that champions government by the people. When a President talks about arresting his political opponents under the pretext of immigration enforcement, it sounds alarmingly like he is using ICE as a political tool rather than a neutral law enforcement body. This perception is corrosive to the public trust. It puts ICE officers in an unwinnable position too – they are caught between fulfilling orders and becoming pawns in political theater.

To be clear, fact must be separated from hyperbole. Despite the administration’s harsh rhetoric, we do not have evidence that ICE as an agency is systematically targeting individuals because they are Democrats or immigrants’ rights activists. The cases of Lander, Padilla, Baraka and others can each be framed (by ICE) as responses to specific conduct: allegedly assaulting officers, interrupting a press event, trespassing on private property. But when so many such incidents cluster in a short span – all involving people opposed to Trump’s policies – it strains credulity to call it coincidence. It creates at least the appearance of selective enforcement or intimidation. And appearances matter; they affect the perceived legitimacy of ICE’s work across the board. Even law-abiding immigrants might now fear that ICE is acting more like a secret police than a professional agency. That fear can drive communities further into the shadows, which is counter-productive for public safety (because crimes then go unreported and unaddressed).

From a values perspective, the hallmark of American democracy has been that government power is not unchecked. Law enforcement agencies answer to courts, to legislatures, and to the public. We’ve seen some encouraging signs of the system pushing back where lines may have been crossed: courts enjoining overreach (as with the worship-sites injunction), bipartisan voices condemning mistreatment of officials, and journalists debunking false narratives about protesters. These correctives are essential. They remind us that how we enforce laws is as important as which laws we enforce. A million deportations achieved by brute force and fear would not be a victory for “law and order” if it shreds the fabric of civil liberties and humanity in the process. On the other hand, completely ignoring immigration law undermines the rule of law and can breed chaos. Thus, a middle path must be charted.

Conclusion: Toward Lawful, Ethical Enforcement

Six months into 2025, the United States finds itself in an intense test of the balance between immigration enforcement and democratic integrity. ICE, as the agency at the center of this storm, carries out a mission that is both necessary and inevitably controversial. The recent patterns – aggressive raids, high-profile arrests of officials, and deployment of extraordinary measures – have heightened that controversy to a level not seen in years.

As an outside observer who believes in the importance of immigration control, I also believe strongly in the principles of justice, proportionality, and accountability. What we have analyzed shows a mix of legitimate law enforcement and instances of apparent overreach. On one hand, ICE has showcased why it exists: capturing fugitives, seizing illegal weapons and drugs, breaking up trafficking schemes, and yes, deporting those who violate immigration laws. These actions, when done lawfully and with care, uphold sovereign laws and protect communities – goals any democracy has a right to pursue. On the other hand, when enforcement turns into a blunt instrument wielded without restraint – when due process is rushed or ignored, when force is used where dialogue would suffice, when political opponents are treated as enemies – it undermines the very democratic values it purports to defend.

In the coming months, it will be critical for ICE and the administration to heed the growing chorus of concern. Congress and the courts should exercise their oversight to ensure that ICE’s newfound powers are not misused. Transparency must improve: for instance, if agents wear body cameras (a policy some lawmakers have proposed for ICE), it could provide objective records to resolve “he said, she said” disputes like Lander’s and Padilla’s. Clear rules of engagement should be set for interactions with public officials to avoid unnecessary confrontations. And perhaps most importantly, a sense of proportionality should guide operations – the tactics used to arrest a peaceful immigration advocate should differ from those used against a violent cartel member.

The tone of America’s immigration enforcement does not have to be Manichaean – all angel or all devil. There is a rational middle ground where laws are enforced firmly but fairly, where ICE can be effective but restrained by constitutional checks. The year 2025 so far has, unfortunately, seen a lurch toward extremes. In recapturing some equilibrium, the U.S. would do well to remember that how a society upholds the law is a reflection of its character. A nation that knocks down a senator for asking a question sends a message of weakness, not strength – it suggests fear of scrutiny. By contrast, a nation that holds its agents to high standards, even as they perform tough jobs, sends the message that it has confidence in the justice of its cause.

Ultimately, the goal should be an immigration system that is both enforceable and just. Lawful, ethical enforcement is not a naive ideal; it is the only sustainable way for a democracy to handle the divisive issue of immigration. As ICE moves forward, one hopes it will apply not just the letter of the law but also a measure of wisdom in each operation – recognizing the humanity of the communities it operates in and the constitutional rights that protect us all, citizens and non-citizens alike. The true test of this chapter in U.S. history will be whether the nation can secure its borders and uphold its laws without losing the soul of its democracy in the process.

Bibliography

American Civil Liberties Union. 2025. Legal Brief on the Use of the Alien Enemies Act in Immigration Enforcement. Washington, D.C.: ACLU.

Armenta, Amada. 2017. Protect, Serve, and Deport: The Rise of Policing as Immigration Enforcement. Oakland: University of California Press.

Castañeda, Jorge G. 2008. “Immigration and U.S. Foreign Policy.” Foreign Affairs 86 (6): 28–43.

Department of Homeland Security. 2025. DHS Statement on Enforcement Priorities and Protected Areas Policy. Washington, D.C.: Office of Public Affairs.

Dowling, Julie A. and Jonathan Xavier Inda, eds. 2013. Governing Immigration Through Crime: A Reader. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ewing, Walter A., Daniel E. Martínez, and Rubén G. Rumbaut. 2015. The Criminalization of Immigration in the United States. Washington, D.C.: American Immigration Council.

Gonzales, Roberto G. 2016. Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America. Oakland: University of California Press.

Human Rights Watch. 2025. ICE Enforcement and the Alien Enemies Act: An Analysis of Legal Overreach. New York: HRW Publications.

Kanstroom, Daniel. 2012. Aftermath: Deportation Law and the New American Diaspora. New York: Oxford University Press.

Koh, Jennifer Lee. 2020. “The Legal Architecture of Immigration Enforcement.” Georgetown Immigration Law Journal 34 (1): 1–42.

Miller, Todd. 2014. Border Patrol Nation: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Homeland Security. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers.

Motomura, Hiroshi. 2014. Immigration Outside the Law. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ngai, Mae M. 2004. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Noem, Kristi. 2025. Press Briefings on Immigration Enforcement Operations. U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Padilla, Alex. 2025. Senate Floor Remarks on ICE and Democratic Oversight. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Record, June 13.

Pope, Adam. 2023. “Courthouse Arrests and the Rule of Law: A Legal Review.” Yale Law & Policy Review 41 (2): 155–180.

Reich, Gary. 2018. The Politics of Immigration: Identity and Citizenship in Europe and the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reuters. 2025. “ICE Arrests NYC Mayoral Candidate at Immigration Court.” Reuters Wire Service, June 17.

Rosenblum, Marc R., and Doris Meissner. 2014. The Deportation Dilemma: Reconciling Tough and Humane Enforcement. Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute.

Schoenholtz, Andrew I., et al. 2021. Refugee Law and Policy: A Comparative and International Approach. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. 2025. Enforcement and Removal Operations Reports, January–June. Washington, D.C.: ICE Office of Public Affairs.

Wasem, Ruth Ellen. 2020. Immigration Governance in the United States: The Politics of Policy Implementation. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Zilberg, Elana. 2011. Space of Detention: The Making of a Transnational Gang Crisis between Los Angeles and San Salvador. Durham: Duke University Press.

Leave a comment